It is well understood that prisoners, as a group, have significantly worse health than the general population with research confirming that prisoners have higher rates of mental illness, substance use disorders, personality disorders, intellectual disability, acquired brain injuries, autism and cognitive impairment.

Studies have shown that, compared to the general community, prisoners are:

- 3-5 times more likely to have a mental illness [1]

- 10-15 times more likely to have a psychotic disorder [2]

- 20 times more likely to have an acquired brain injury [3]

Studies have also shown that 42% of prisoners have a psychiatric risk rating indicating mental health concerns [4].

The challenge in most jurisdictions is that there are few, if any, purpose built forensic mental health facilities; and where they do exist, demand greatly outstrips supply. As a result, many prisoners with acute mental health concerns are placed in accommodation that only serves to aggravate their mental health conditions. Some of the most moving and emotional project briefings we’ve experienced have been for specialist mental health facilities, where experienced custodial and forensic mental health staff have had tears in their eyes as they’ve spoke about some of the individual cases where they’ve been unable to find an appropriate place for some prisoners, which has at times led to tragic outcomes.

So how do we as designers make a difference for mentally ill offenders?

How can the design of mental health facilities aid recovery?

Here is a list of 6 proven design strategies that we’ve employed in our projects to create therapeutic mental health environments that aid recovery and rehabilitation.

1. Design for Therapy

Our physical environment is constantly influencing our emotions and general well-being. The layout of a room, space or building directly affects a patient’s perception of safety and privacy and impact their willingness to self-disclose and to build therapeutic rapport with clinicians and therapists. Poor layouts can exacerbate feelings of otherness, reduce communication, and have poor therapeutic outcomes.

Thomas Embling Mental Health Hospital, MAAP Architects & DesignInc

Careful consideration of the layout and amenity of a room is especially important for spaces where therapy and counselling services are facilitated. Consideration of colour, materials, lighting, aspect and furnishings can all help to create a comfortable therapeutic experience for emotionally vulnerable individuals.

The integration of sensory modulation elements that utilise weighted, movement, tactile, vibrating, squeeze, and auditory modalities to manage distress and agitation is a proven approach to regulate and de-escalate patient behaviours.

Effective sensory modulation practice increases service users’ awareness of their sensory preferences and assists them to manage their arousal through the application of sensory strategies. [5]

2. Prospect & Refuge

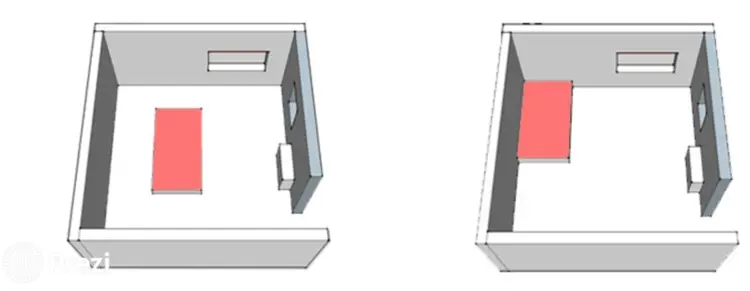

Within indoor and outdoor communal spaces, the placement of furniture against walls and in smaller groups can create pockets of privacy where patients can withdraw themselves and have a sense of safety and seclusion. Long distance views to landscape areas beyond the communal spaces can further enhance the sense of prospect and comfort. Within bedrooms, the placement of beds against walls with a clear line of sight to the door, can help to provide a sense of physical security and comfort for patients with heightened paranoia.

Ginger Curtis on urbanologydesigns.com

3. Space

The size of indoor and outdoor communal spaces should be generous to enable patients to move around within the unit without feeling crowded or overly constrained.

The need for space cannot be overemphasised as a means of reducing the potential for aggressive behaviour, by way of wide corridors and recreation areas large enough to avoid crowding. [5]

The dayroom and courtyard spaces of forensic mental health facilities should be designed to facilitate communal gatherings of the cohorts within each unit but should also incorporate smaller pockets of privacy that patients can withdraw to whilst still being observed by custodial or clinical staff. The scale and volume of communal spaces should be varied to provide interest and to cater for the differing social and sensory preferences of the patients.

Ravenhall Correctional Centre, Guymer Bailey Architect. Photography by Scott Burrows

4. Natural Light and Artificial Lighting

Integral to biophilic design is the provision and quality of natural and artificial lighting, including the impact that lighting has on circadian rhythms.

Variations in ambient illumination impact behaviours such as rest during sleep, and activity during wakefulness, as well as their underlying biological processes. Rather recently, the availability of artificial light has substantially changed the light environment, especially during evening and night hours with nocturnal electric lighting shown to alter circadian rhythms and sleep patterns. On the other hand, light can also be used as an effective and non-invasive therapeutic option, to improve sleep, mood and general well-being.

Recently we have been working with lighting controls that adjust the colour tone and brightness of electric lighting to reflect natural lighting, and this has been shown to assist in regulating circadian rhythms, normalising sleep patterns and reducing Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD).

Rivergum Residential Treatment Centre, Guymer Bailey Architects. Photography by Scott Burrows

5. Connection to Nature

Windows of bedrooms and communal living spaces that are positioned to capture views to landscape areas beyond the building have been shown to help to regulate patient behaviour. Being in nature, or even viewing scenes of nature, reduces anger, fear, and stress and increases pleasant feelings. Exposure to nature not only makes patients feel better emotionally, it contributes to their physical wellbeing, reduces blood pressure, heart rate, muscle tension, and the production of stress hormones.

The best form of interior design is a window!

Courtyards should be designed to reduce the patients’ sense of being contained and provide some form of sensory stimulus such as textured ground surfaces, shaded areas and attractive but sturdy fixed furniture. Where permitted by spatial and security constraints, raised garden beds, grassed terraces and undulations in the ground plane should be considered to create more defined spaces within the landscape providing they do not hinder passive surveillance.

Ravenhall Correctional Centre, Guymer Bailey Architect. Photography by Scott Burrows

6. Acoustics

The acoustic environment of a correctional centre is unique. Due to the need for the buildings to be constructed from robust, hard wearing and durable materials; communal spaces, corridors, cells and bedrooms generally have high reverberation rates. As a result, the sound of buzzing electric locks, clanging heavy steel doors, conversations and even footsteps are amplified throughout the patient areas.

Whilst this may just be an annoying nuisance for some, it can also be a recurring trigger that causes the behaviour of patients with a mental health illness to escalate. As such, special consideration is provided to managing acoustic reverberation within mental health and high needs units through careful use of appropriate absorptive material, design that avoids rectangular forms and acoustic separation between spaces.

What does the future hold?

With increasing community recognition of mental health conditions and the reduction in the stigma associated with treatment, the need for mental health services across all segments of the community will continue to grow. As the demand rises, there will be an ongoing need for new specialist facilities designed to cater for the unique needs of patients with a wide range of mental health conditions; as well as a need to upgrade existing facilities to introduce best practice rehabilitative design.

References

- Victorian Ombudsman Report (2014). Investigation into deaths and harm in custody, p.111.

- Victorian Ombudsman Report (2015) – Investigation into the rehabilitation and reintegration of prisoners in Victoria, p. 32.

- Victorian Ombudsman Report (2015) – Investigation into the rehabilitation and reintegration of prisoners in Victoria, p. 34.

- Victorian Ombudsman Report (2014). Investigation into deaths and harm in custody, p.114.

- Sensory Modulation in Acute Mental Health Wards : Te Pou

By Craig Blewitt and Andrew Greig